What rights do landowners have when a pipeline company takes part of their property by eminent domain? As I mentioned on Monte Belmonte's show on the River, although federal law governs the taking itself, state law determines the meaning of "just compensation." What, then, is "just compensation" for an easement over part of your land?

Here in Massachusetts the courts start their analysis with the applicable statute, M.G.L.c.79, s.12, which provides that in the case of a partial taking the assessment shall include "damages to the part not taken." So the landowner needs to show the diminution in the fair market value of the whole parcel (both the taken part and the remaining part). In other words, what would a hypothetical willing buyer pay for the property as a whole after it had been on the market for a reasonable length of time. At this point readers may wonder how a judge would arrive at that hypothetical buyer's price. The following case provides some guidance.

When the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts considered this issue, it decided to take into account several factors, including (1) "stigma," i.e public fear of potential hazards (even exaggerated fears based on misinformation) and (2) the possible additional construction expenses and the "administrative hassle" of having to abide by the company's rules. The figure the judge ordered was far in excess of what the company deemed reasonable, so the company appealed. But the Court of Appeals for the First Circuit affirmed the judge's decision. Portland Natural Gas Transmission Sys. v. 19.2 Acres of Land in Haverhill, 195 F.Supp.2d 314 (D.Mass. 2002) aff'd 318 F.3d 279 (1st Cir. 2003).

What does this mean for landowners in Berkshire and Franklin Counties whose properties the underground pipeline might cross? When preparing for the eminent domain case, they should make sure their attorneys have garnered abundant evidence of how the taking will diminish the fair market value of their property, including photographs and testimony from expert and lay witnesses alike. In putting their evidence together they should bear in mind that the court should take into account the "stigma" and "hassle" factors.

If you have questions about what might constitute "stigma" and "hassle," please feel free to post a comment/call/email.

Wednesday, February 19, 2014

Monday, February 17, 2014

New Pipeline in the Pipeline for Western Massachusetts: Federal Law

According to TV and print media, a new natural-gas pipeline might soon stretch 250 miles across northern

Massachusetts, winding its way under a dozen or so towns in

Berkshire and Franklin Counties.

Although the project would generate hundreds of construction

jobs, a unanimous Bay State welcome seems unlikely. Environmentalists will point to the

impact of fossil fuels on the climate and perhaps abutters will raise concerns about

possible leaks and explosions. Some property-owners might be inclined to hold out, for reasons of high-mindedness or high expectations. Whatever their differences of opinion and interest, proponents and opponents alike should note that a federal law, the Natural Gas Act, gives pipeline owners an important advantage: if the company and the landowner cannot reach agreement the company can simply take the land, exercising a power usually reserved to governments as opposed to private actors. Here is a link to the relevant

provision of the statute: 15 U.S.C. §717f(h).

In enacting this statute, Congress created a comprehensive

national framework. So claims and objections based on state laws – even on state constitutions

– cannot stand in the way of a natural-gas pipeline.

The company cannot engage in any takings quite yet. First it

has to obtain a certificate of “public convenience and necessity” from the

Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. But potential holdouts, beware: From that point onward, armed with its certificate,

Tennessee Gas Pipeline Company would have the right to take what it needs by

eminent domain.

Tuesday, July 9, 2013

Affirmative Action after Fisher

A stable society depends on the rule of law, which involves, among other things, legal certainty. This is a simple principle that means people should have a reasonable sense of what is lawful and what is not. It also depends on the general public having confidence that the law enjoys some relationship -- not necessarily close, but at least a passing one -- to common sense.

But a recent decision about affirmative action in higher education has given the public cause to scratch their heads in puzzlement.

Discrimination law is complex, and nobody should expect judicial opinions on the subject to be as pat and trite as a politician's soundbite. But the rule of law requires that ordinary people of reasonable intelligence should at least be able to follow the rationale for a judicial decision even if they do not agree with it. The case of Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin falls short of this standard.

In Fisher, the Supreme Court held that the educational benefits of racial diversity can justify a state university in using race as a factor in its admissions process, but only if there are "no workable race-neutral alternatives." The holding in Fisher leaves informed, intelligent individuals wondering how, when, and why some (but not other) race-based classifications are acceptable, and grasping for a way to make sense of the plain-English version of the decision, namely that a state university must try to achieve racial diversity without considering race.

But a recent decision about affirmative action in higher education has given the public cause to scratch their heads in puzzlement.

.jpg) |

| Fisher: a puzzling decision |

In Fisher, the Supreme Court held that the educational benefits of racial diversity can justify a state university in using race as a factor in its admissions process, but only if there are "no workable race-neutral alternatives." The holding in Fisher leaves informed, intelligent individuals wondering how, when, and why some (but not other) race-based classifications are acceptable, and grasping for a way to make sense of the plain-English version of the decision, namely that a state university must try to achieve racial diversity without considering race.

As Justice Kennedy noted at the very beginning of the Court's opinion, the University of Texas at Austin "considers race as one of various factors in its undergraduate admissions process." Precedent entitles it to do so, even though racial classifications trigger strict scrutiny under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. But in reviewing the University's process, the Court of Appeals had failed to "apply the correct standard of strict scrutiny." What then is the "correct standard," which the the Court of Appeals should have applied? It is this, said the Supreme Court:

Some background is helpful at this point. Affirmative action involves making decisions on the basis of racial classifications. When the government uses a racial classification, the courts will apply the "strict scrutiny" test to determine whether that use is consistent with the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Thirty-five years ago the Supreme Court of the United States held that in the context of higher education a state university that uses race as one of its admissions criteria must show that the use is "narrowly tailored to serve a compelling governmental interest." Regents of Univ. of Cal. v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 299 (1978). And what is that "compelling governmental interest"? The "educational benefits of student body diversity," said the Supreme Court in Gratz v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 244 (2003) and Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306, 325 (2003).

It is important to note that the plaintiff in Fisher did not challenge this notion that the "educational benefits of student body diversity" rise to the level of a compelling governmental interest. A compelling governmental interest is part of the strict scrutiny test. It is, by definition, a higher standard than the "legitimate" and "important" governmental interests that form part of the rational-basis and intermediate scrutiny tests respectively. Grutter and Gratz remain authority for the proposition that the educational benefits of racial diversity constitute a compelling -- not merely legitimate or important -- governmental interest. In their separate concurrences, Justices Thomas and Scalia both indicated that they would have welcomed the opportunity to revisit this issue.

In his concurrence, Justice Thomas observed that the only other situations to qualify as compelling governmental interests sufficient to justify racial classifications were national security and the duty to remedy past racial discrimination. He pointed out that in the 1950s and 60s when segregationist state governments claimed that desegregation would force schools to close, the Supreme Court "was unmoved by this sky-is-falling argument." If even the very survival of a university is not a governmental interest sufficiently compelling to justify racial discrimination, Justice Thomas wrote, it follows that the state "cannot have a compelling interest in the supposed benefits that might accrue to that university from racial discrimination." Justice Thomas enunciates a clear argument that even his critics would concede is internally consistent. Just as clear and consistent as Justice Thomas's concurrence is the dissent.

Unlike Justice Thomas, Justice Ginsburg supports affirmative action. She pointed out that requiring universities to employ race-neutral means to achieve an obviously race-conscious end encourages them to "resort to camouflage." Instead, the courts should be more candid. On the subject of strict scrutiny, Justice Ginsburg wrote that judges should not subject all racial classifications to the same standard of judicial review, letting them distinguish between those "designed to benefit... [and those designed to] burden a historically disadvantaged group." Even though it rests on the assumption that judges are able to recognize a burden when they see one, this approach does not consider the rejection of Asian and White students as a burden, even though it is the corollary of the benefit to admitted Black students.

Like Justice Ginsburg, the legal scholar Randall Kennedy believes that "reparatory justice" not educational diversity is the moral and intellectual justification for affirmative action. He describes Abigail Fisher, the plaintiff in the Fisher case, as "to a small extent disadvantaged... [b]ut for the purpose of aiding a commendable mission of racial healing not for the purpose of putting her down on account of her race." He shares Justice Ginsburg's belief that one can distinguish between invidious discrimination and benign racial distinctions, and he would not put the discrimination Abigail Fisher experienced in the invidious category. This is an approach Justice Thomas disagrees with fundamentally: "I think the lesson of history is clear: Racial discrimination is never benign."

Justice Thomas's reasoning may have a closer connection to common sense than the opinion of the Court, as may Justice Ginsburg's. But the concurrence and the dissent are not the law. The majority (including Justices Thomas and Scalia) signed on to an opinion that (a) justifies affirmative action in higher education on the basis that the educational benefits of diversity constitute a compelling governmental interest; (b) requires a university that wishes to achieve the educational benefits of diversity to attempt to do so by race-neutral means; and (c) allows the university to use race only if no workable, race-neutral alternative would produce the educational benefit of diversity.

People who differ fundamentally on the issue of affirmative action can at least agree that the decision does nothing to promote legal certainty. The rule of law requires a more well-reasoned, internally consistent, readily comprehensible decision than the Court provided in Fisher.

"[S]trict scrutiny imposes on the University the ultimate burden of demonstrating, before turning to racial classifications, that available, workable, race-neutral alternatives do not suffice."Reducing the holding to its essence, universities are free to aim for racial diversity so long as they do not use race in the process. Only if there is no "available, workable race-neutral alternative" that will produce the educational benefits of racial diversity (and not merely diversity itself) may they use race as one of their admissions criteria. This standard is hard to understand in theory, almost impossible to apply in practice, and the most likely field for the next battle over affirmative action.

Some background is helpful at this point. Affirmative action involves making decisions on the basis of racial classifications. When the government uses a racial classification, the courts will apply the "strict scrutiny" test to determine whether that use is consistent with the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Thirty-five years ago the Supreme Court of the United States held that in the context of higher education a state university that uses race as one of its admissions criteria must show that the use is "narrowly tailored to serve a compelling governmental interest." Regents of Univ. of Cal. v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 299 (1978). And what is that "compelling governmental interest"? The "educational benefits of student body diversity," said the Supreme Court in Gratz v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 244 (2003) and Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306, 325 (2003).

It is important to note that the plaintiff in Fisher did not challenge this notion that the "educational benefits of student body diversity" rise to the level of a compelling governmental interest. A compelling governmental interest is part of the strict scrutiny test. It is, by definition, a higher standard than the "legitimate" and "important" governmental interests that form part of the rational-basis and intermediate scrutiny tests respectively. Grutter and Gratz remain authority for the proposition that the educational benefits of racial diversity constitute a compelling -- not merely legitimate or important -- governmental interest. In their separate concurrences, Justices Thomas and Scalia both indicated that they would have welcomed the opportunity to revisit this issue.

In his concurrence, Justice Thomas observed that the only other situations to qualify as compelling governmental interests sufficient to justify racial classifications were national security and the duty to remedy past racial discrimination. He pointed out that in the 1950s and 60s when segregationist state governments claimed that desegregation would force schools to close, the Supreme Court "was unmoved by this sky-is-falling argument." If even the very survival of a university is not a governmental interest sufficiently compelling to justify racial discrimination, Justice Thomas wrote, it follows that the state "cannot have a compelling interest in the supposed benefits that might accrue to that university from racial discrimination." Justice Thomas enunciates a clear argument that even his critics would concede is internally consistent. Just as clear and consistent as Justice Thomas's concurrence is the dissent.

Unlike Justice Thomas, Justice Ginsburg supports affirmative action. She pointed out that requiring universities to employ race-neutral means to achieve an obviously race-conscious end encourages them to "resort to camouflage." Instead, the courts should be more candid. On the subject of strict scrutiny, Justice Ginsburg wrote that judges should not subject all racial classifications to the same standard of judicial review, letting them distinguish between those "designed to benefit... [and those designed to] burden a historically disadvantaged group." Even though it rests on the assumption that judges are able to recognize a burden when they see one, this approach does not consider the rejection of Asian and White students as a burden, even though it is the corollary of the benefit to admitted Black students.

Like Justice Ginsburg, the legal scholar Randall Kennedy believes that "reparatory justice" not educational diversity is the moral and intellectual justification for affirmative action. He describes Abigail Fisher, the plaintiff in the Fisher case, as "to a small extent disadvantaged... [b]ut for the purpose of aiding a commendable mission of racial healing not for the purpose of putting her down on account of her race." He shares Justice Ginsburg's belief that one can distinguish between invidious discrimination and benign racial distinctions, and he would not put the discrimination Abigail Fisher experienced in the invidious category. This is an approach Justice Thomas disagrees with fundamentally: "I think the lesson of history is clear: Racial discrimination is never benign."

Justice Thomas's reasoning may have a closer connection to common sense than the opinion of the Court, as may Justice Ginsburg's. But the concurrence and the dissent are not the law. The majority (including Justices Thomas and Scalia) signed on to an opinion that (a) justifies affirmative action in higher education on the basis that the educational benefits of diversity constitute a compelling governmental interest; (b) requires a university that wishes to achieve the educational benefits of diversity to attempt to do so by race-neutral means; and (c) allows the university to use race only if no workable, race-neutral alternative would produce the educational benefit of diversity.

People who differ fundamentally on the issue of affirmative action can at least agree that the decision does nothing to promote legal certainty. The rule of law requires a more well-reasoned, internally consistent, readily comprehensible decision than the Court provided in Fisher.

Wednesday, March 13, 2013

Desegregation: a new rule

Advocates of desegregation should take heart, and planners should take notice, because at last it's official: Land-use policies that perpetuate residential segregation are illegal. A new rule from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) clearly spells out that the Fair Housing Act prohibits practices that have a discriminatory effect (disparate impact), even if there was no intent to discriminate.

Confirming the way most federal courts had long interpreted the statute, HUD's new rule states that "[a] practice has a discriminatory effect where it actually or predictably results in a disparate impact on a group of persons or creates, increases, reinforces, or perpetuates segregated housing patterns because of race, color, religion, sex, handicap, familial status, or national origin" 24 CFR 100.500(a), Subpart G. This applies to public and private entities alike, so it covers not only city councils and local housing authorities but also housing developers.

Federal courts generally apply a three-part burden-shifting formula to decide whether a land-use policy violates the statute's discriminatory-effects prohibition, and this is the course that HUD decided to follow. First the plaintiff has to show that the practice "caused or predictably will cause a discriminatory effect." The burden then shifts to the respondent to prove that the practice "is necessary to achieve one or more [of the respondent's] substantial, legitimate, nondiscriminatory interests." If the respondent succeeds, the burden shifts back to the plaintiff to prove that the respondent could serve those interests "by another practice that has a less discriminatory effect."

On the one hand, this does not represent a new departure or a substantive change to the federal law. But, on the other hand, it certainly helps plaintiffs who are trying to show that a zoning decision would violate the Fair Housing Act even if the city officials had no intention of acting in a racially discriminatory way. In practice, this may encourage challenges to the planning policies that undergird the de facto segregation of the public schools in and around Springfield, Massachusetts.

As before, any ordinance, bylaw, policy, or practice is open to a courtroom attack if it "creates, increases, reinforces, or perpetuates segregated housing patterns." Now, however, desegregation advocates will have an easier time defeating the customary motion to dismiss.

Confirming the way most federal courts had long interpreted the statute, HUD's new rule states that "[a] practice has a discriminatory effect where it actually or predictably results in a disparate impact on a group of persons or creates, increases, reinforces, or perpetuates segregated housing patterns because of race, color, religion, sex, handicap, familial status, or national origin" 24 CFR 100.500(a), Subpart G. This applies to public and private entities alike, so it covers not only city councils and local housing authorities but also housing developers.

Federal courts generally apply a three-part burden-shifting formula to decide whether a land-use policy violates the statute's discriminatory-effects prohibition, and this is the course that HUD decided to follow. First the plaintiff has to show that the practice "caused or predictably will cause a discriminatory effect." The burden then shifts to the respondent to prove that the practice "is necessary to achieve one or more [of the respondent's] substantial, legitimate, nondiscriminatory interests." If the respondent succeeds, the burden shifts back to the plaintiff to prove that the respondent could serve those interests "by another practice that has a less discriminatory effect."

On the one hand, this does not represent a new departure or a substantive change to the federal law. But, on the other hand, it certainly helps plaintiffs who are trying to show that a zoning decision would violate the Fair Housing Act even if the city officials had no intention of acting in a racially discriminatory way. In practice, this may encourage challenges to the planning policies that undergird the de facto segregation of the public schools in and around Springfield, Massachusetts.

|

| Springfield: Some of the most segregated schools in the nation |

As before, any ordinance, bylaw, policy, or practice is open to a courtroom attack if it "creates, increases, reinforces, or perpetuates segregated housing patterns." Now, however, desegregation advocates will have an easier time defeating the customary motion to dismiss.

Friday, January 18, 2013

This should be easy

Some aspects of intellectual property law are inherently complex. But other areas could be -- and should be -- much simpler. For example, you would think the law would have a crystal clear answer to this question: When a retailer is selling something produced by a famous manufacturer and wants to advertise the fact, is the retailer allowed to use the manufacturer’s name in its advertisements?

Reasonable readers may well ask themselves why this isn't settled law, something the trademark statute or an early decision interpreting the statute must have established long ago. But it was this very question that the Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit considered this month (January 2013) in Swarovski Aktiengesellschaft v. Building #19, Inc. Here are the facts:

The plaintiff, Swarovski, makes crystal products. The defendant, Building #19, bought some Swarovski products in order to sell them at its stores. To that end, Building #19 designed some advertisements, which informed the public that (a) it was offering Swarovski products for sale; and (b) Building #19 had no connection to Swarovski and was not an authorized Swarovski dealer. The advertisements prominently featured the mark Swarovski (replete with the circled-R registered trademark symbol). The disclaimer was much less prominent. Swarovski sued Building #19 and managed to obtain a preliminary injunction.

Reasonable readers may well ask themselves why this isn't settled law, something the trademark statute or an early decision interpreting the statute must have established long ago. But it was this very question that the Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit considered this month (January 2013) in Swarovski Aktiengesellschaft v. Building #19, Inc. Here are the facts:

The plaintiff, Swarovski, makes crystal products. The defendant, Building #19, bought some Swarovski products in order to sell them at its stores. To that end, Building #19 designed some advertisements, which informed the public that (a) it was offering Swarovski products for sale; and (b) Building #19 had no connection to Swarovski and was not an authorized Swarovski dealer. The advertisements prominently featured the mark Swarovski (replete with the circled-R registered trademark symbol). The disclaimer was much less prominent. Swarovski sued Building #19 and managed to obtain a preliminary injunction.

|

| Crystal figurine by... oh, wait. |

Yes, indeed: Swarovski persuaded a United States district court judge to prohibit Building #19 from using the word Swarovski in an ad that stated, truthfully, that the company was selling Swarovski crystal collectibles. How, reasonable readers may wonder, was Building #19 supposed to promote its perfectly lawful sale of Swarovski products without using the name Swarovski? That is a question the district court can mull over at its leisure now that the Appeals Court has quashed the preliminary injunction.

In trademark law, the term we use to describe this situation is “nominative fair use.” This is the judge-made principle that allows you to use another person's trademark so long as you're not trying to mislead anyone. The Appeals Court noted that although the First Circuit recognized nominative fair use it had “never endorsed any particular version of the doctrine.” I respectfully submit that now would be a good time. Business owners, creators, and the general public would appreciate some certainty.

Friday, November 16, 2012

Why remember William H. Lewis?

Before we say goodbye to 2012, the year in which we re-elected our first African-American President, I would like to mention an important centenary in civil rights law. One hundred years ago William H. Lewis, a graduate of Amherst College and Harvard Law School, completed his service as the first African-American Assistant Attorney General of the United States.

It was President William Howard Taft who appointed Lewis, and President Woodrow Wilson, the winner of the 1912 election, who fired him. As Professor J. Clay Smith, Jr., points out in Emancipation: The Making of the Black Lawyer, 1844-1944, before leaving the White House, Taft tried, unsuccessfully, to persuade the Governor of Massachusetts to appoint Lewis to the bench.

Although Lewis never became a judge, he helped shape the state's anti-discrimination statutes. Even as a law student in the mid-1890s, Lewis was already part of Boston's network of African-American civil rights activists. Whether to bring a test case or just by chance, he visited a Cambridge barber shop for a haircut. When the owner refused him service Lewis and his allies -- including State Representative Robert Teamoh -- lobbied to add barber shops to the list of places where discrimination was unlawful.

The lobbying paid off. So even before his stint as a state legislator in 1902, Lewis had left an imprint on the statute book. Those of us who practice anti-discrimination law can be thankful for his efforts.

|

| William H. Lewis, Esq. |

It was President William Howard Taft who appointed Lewis, and President Woodrow Wilson, the winner of the 1912 election, who fired him. As Professor J. Clay Smith, Jr., points out in Emancipation: The Making of the Black Lawyer, 1844-1944, before leaving the White House, Taft tried, unsuccessfully, to persuade the Governor of Massachusetts to appoint Lewis to the bench.

Although Lewis never became a judge, he helped shape the state's anti-discrimination statutes. Even as a law student in the mid-1890s, Lewis was already part of Boston's network of African-American civil rights activists. Whether to bring a test case or just by chance, he visited a Cambridge barber shop for a haircut. When the owner refused him service Lewis and his allies -- including State Representative Robert Teamoh -- lobbied to add barber shops to the list of places where discrimination was unlawful.

The lobbying paid off. So even before his stint as a state legislator in 1902, Lewis had left an imprint on the statute book. Those of us who practice anti-discrimination law can be thankful for his efforts.

Wednesday, October 31, 2012

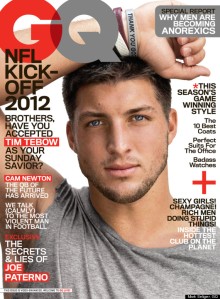

Tebowing Trademark Takeaways: Three Lesons

New York Jets quarterback Tim Tebow is in the news over rumors of a trade. Before that, the headlines were about his trademark. Wherever Tebow plays football, it seems a safe bet that he will be trying to control the use of the word “Tebowing,” a term that describes the Christian athlete’s practice of dropping to one knee in prayer. For fans and non-fans, faithful and faithless alike, Tebow’s recent experience with trademark law has three lessons.

But before the lessons, some background. In December 2011, Tebow filed a set of intent-to-use applications with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) for the words “Tim Tebow” in connection with products such as jewelry, clothing, DVDs, and stationery, and services such as online seminars. The USPTO published three of the applications for opposition in the Official Gazette on October 16, 23, and 30 respectively. If nobody objects during the 30-day opposition period, Tebow’s name will become a federally registered trademark in three different classes in time for the holidays.

But Tim Tebow’s are by no means the only Tebow-related applications the USPTO has on its docket. There are currently seven live (and three dead) applications for the mark “Tebowing,” a verb that entered the lexicon in October 2011, according to Wikipedia. That was the authority the USPTO cited when it rejected the trademark application of Jared Kleinstein on February 22, 2012, a fact replete with irony in view of the fact that it was Kleinstein who – according to Wikipedia – coined the term Tebowing.

Kleinstein had filed his application (serial no. 85458244) to register “Tebowing” on October 27, 2011. Along with his application he submitted a screenshot showing a list of t-shirts he had sold that day via Café Press.

But before Kleinstein’s application could make it to the Official Gazette, Tim Tebow himself intervened. In January 2012, Tebow’s attorney sent the USPTO three letters of protest complaining that Kleinstein’s mark would cause consumer confusion: Consumers would presume a connection between the trademark and Tim Tebow. As evidence, Tebow’s counsel pointed to the athlete’s sponsorship deals with Nike, Jockey Apparel, and Electronic Arts. The USPTO concurred and refused Kleinstein’s application because it implied a false connection with a living individual, contrary to 15 U.S.C. section 1052(d).

Was that the end of Kleinstein’s application? No, it rose again and now –made reincarnate – has a new applicant, namely XV Enterprises, an LLC organized in Florida, with a business address of 5082 Hampden Avenue, Suite 115, Denver, Colorado. As the Hampden Avenue neighborhood might suggest (Temple Sinai on one side and Bethany Lutheran Church on the other) the owner of XV Enterprises is Tim Tebow.

So how did Tim Tebow’s company end up with Jared Kleinstein’s trademark application? The process seems to have involved nothing more miraculous than money. On May 10, 2012, Kleinstein assigned his trademark application to XV Enterprises “for good and valuable consideration.” Unfortunately for those of us who are curious about these things, the assignment does not state the number of dollars that moved from Tim Tebow to Jared Kleinstein.

With Tebow’s XV Enterprises as the applicant, the USPTO published “Tebowing” for opposition October 9, 2012. The 30 day opposition period runs until November 8, so if you have a legitimate claim to the mark “Tebowing” and do not wish Tim Tebow to acquire the exclusive, nationwide right to use it in commerce, you should act swiftly. In the meantime, what lessons can we draw from the mark’s sojourn in the USPTO?

1. Letter of Protest

Tim Tebow’s lawyer did not wait until the post-publication opposition period. He filed a letter of protest, a powerful weapon that enables third parties – not only the owners of competing marks – to step into the USPTO’s examination process at an early stage. Although it is an informal document, a letter requires factual, objective evidence, not mere opinion. But the evidentiary standards are not onerous. So trademark owners and concerned citizens who learn of applications with the potential to cause consumer confusion should not sit on their hands.

2. Assignment

Jared Kleinstein assigned his mark and “the goodwill associated with it” to XV Enterprises. As any intellectual property practitioner knows, you cannot assign a trademark in gross. What does that mean? It means that when you transfer trademark rights, you must convey not simply the mark, but also the goodwill associated with it. The “amorphous goodwill concept,” as Professor Robert Bone calls it, refers to a mark’s consumer loyalty, but remains “abstract, and notoriously difficult to define.” Business owners and their attorneys should not fret unduly about the precise meaning of the word; all we need to remember is to include it in the assignment.

3. Right of Publicity

Tim Tebow is a resident of New Jersey, according to his Facebook page. New Jersey is one of the states that recognizes the right of publicity, which allows individuals to control the commercial exploitation of their name and likeness. Unlike federal trademark protection, the right of publicity does not depend on you registering your name anywhere, filing renewals, paying a fee, or using it in interstate commerce. These are clear advantages. On the other hand, whether you actually have a right of publicity depends on where you live. Almost half the states do not recognize it. Of those that do, only some have enacted statutes to delineate its scope; in the others it remains a common-law right and, therefore, less predictable. As a practical matter then, if your name has value in the marketplace, registering it as a trademark would be wiser than simply relying on the right of publicity.

Finally, it is worth remembering the power of parody. Although the Lanham Act does not explicitly provide fair-use exceptions like parody the way the Copyright Act does, judges are tending to imply it so as to uphold the First Amendment. This evolving area of law may affect Tim Tebow, because among the other entrepreneurs seeking to turn Tebow’s fame to their pecuniary advantage is Daniel Gordon of New Jersey. He has applied to register the word Tebow within the outline of a fish (think Jesus fish and Darwin fish). Does he have a prayer? Stay tun

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)